I Am Hannibal, the Protagonist

I’ve been violating international humanitarian law since elementary school. Okay – maybe not really, but let’s be real, you can do some real fucked up shit in The Sims. Once I learned I could be the bringer of death and despair to the poor virtual characters on my screen, I became the judge, jury, and executioner of a sick and twisted form of justice only I truly understood the rules of – and those rules changed often, depending on my mood. Looking back, I imagined those interactions between myself and my Sims sounding somewhat like the conversations between Hannibal Lecter and his foil, Clarice Starling, in Silence of the Lambs.

Hannibal (me): What if I did it for you?

Clarice (my Sim, a perfect angel who has done no wrong): Did what?

Hannibal (me): Harmed them, Clarice. The ones who've harmed you. What if I made them scream apologies? No, I shouldn't even say it because you'll feel - with your perfect grasp on right and wrong - that you were somehow [...] - even though you wouldn't be.

If a god exists in the world of the Sims, I hope it had mercy on the souls of the countless NPCs I marched to their deaths via fire, drowning, starvation, and more. I did the regular ol’ tactic of forcing a Sim to take a swim before removing the ladder to get out, watching them swim until finally, exhausted, they’d sink below the surface forever. I’d force low-skilled Sims to fix broken dishwashers with puddles underneath, more often than not leading to electrocution. One Sim cheated on another Sim I’d taken a liking to, so I took him into the backyard and built walls around him – that character eventually pissed himself, then died of starvation in the dark. These only scratch the surface of the atrocities I’ve committed in this game.

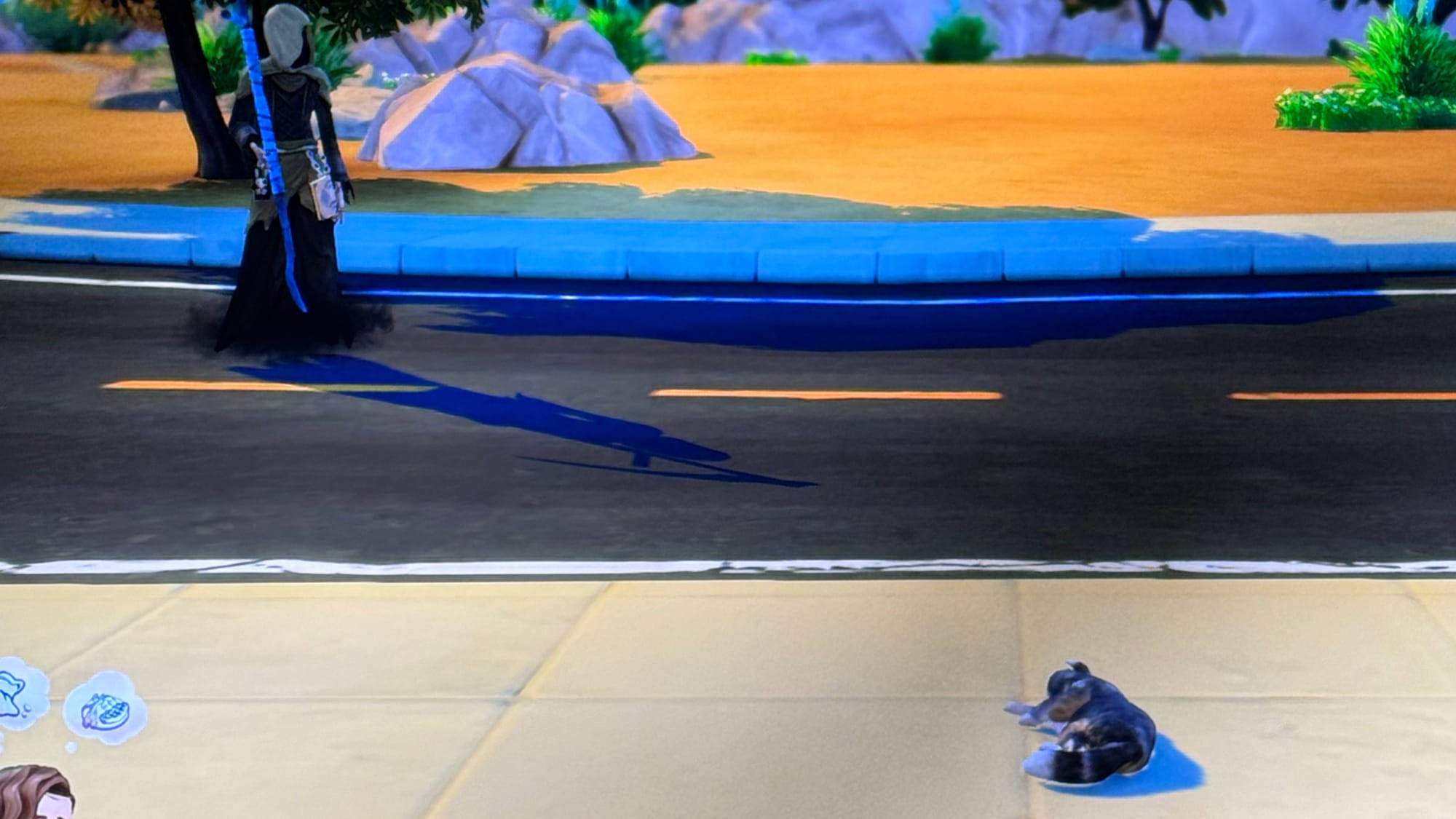

The horrors I unleashed on the game’s NPCs were cruel, unusual, and grimly, grimly fun. I imagine even the game’s anthropomorphic version of Death, the Grim Reaper, was giving my character a little bit of side-eye while he cleaned up the messes I left behind.

I’ve been playing the franchise on and off ever since Bustin’ Out released on PlayStation 2 back in 2003. I remember, at 8, being enamored with the idea of pestering a Sim so much that you could start flipping the bird at them when their relationship meter got low enough (again, I was 8, so flipping the bird at someone was considered A Real Big Deal). I loved the challenge of figuring out the likes and dislikes of each different NPC so I could bend them to my will – I mean, interact with them in a totally normal and healthy way.

I never played with dollhouses or the equivalent when I was a kid, but a couple friends of mine have mentioned occasionally inflicting similar tortures on their helpless dolls as they acted out ridiculously dramatic narratives. A girlfriend of mine, beautiful and dazzling and brilliant and successful, once told me she’d cut all the hair off of her Barbies and throw them downstairs for the dogs.

I realize the sample size is, “Friends of Abby, who has just admitted to committing unimaginable cruelties to her NPC companions,” but, you know, you take what data you can get and make your inferences accordingly.

The Sims as a Lab for Self

Maybe it’s no coincidence that The Sims felt like such an easy fit for me as a kid. Long before computers rendered little people on our screens, children were already experimenting with control, relationships, and morality through dollhouses, action figures, and imaginary friends. Developmental psychologists call this sociodramatic play: the practice of staging scenarios, inventing conflicts, and trying on roles. On the surface, it looks like harmless chaos – Barbies with hacked-off hair tumbling down staircases, soldiers endlessly falling on a battlefield, or dolls trapped in elaborate plastic castles – but underneath, kids are rehearsing the dramas of real life. They’re learning what it means to negotiate power, to reward and punish, to test boundaries, and to imagine alternative selves.

Turns out, neuroscience shows that when kids play pretend, their brains light up in the same places adults use for empathy. Which tracks – I’ve worked myself up into a rage over fake scenarios that come to mind as I’m trying to fall asleep (and don’t you pretend you haven’t).

Psychologists like Sara Smilansky have documented how make-believe games help children practice the skills of negotiation, conflict resolution, and empathy. In other words: a dollhouse, a sandbox, or a family of digital Sims isn’t just a toy – it’s a lab. And if children in the 1950s were punishing their dolls for “misbehaving,” then it’s not much of a leap to understand why an 8-year-old me might take such gleeful ownership over the fates of my Sims like a Joffrey-esque godchild on a sugar high.

Joffrey (me): I'm going to give you a present. After I raise my armies and kill your traitor brother, I'm going to give you his head as well.

Developmental psychologists argue that dollhouses, action figures, and yep – even The Sims – are less about the toys themselves and more about what they let us do with them. Pretend play is a kind of mirror play: a way to project our fears, hopes, and values onto something external so we can look at them more clearly. Children’s brains light up in the same empathy and social-processing regions when they’re pretending as when they’re engaging with real people. And scholars studying sandbox games point out that adults never really stop doing this – we’re pretty much just swapping plastic dolls for digital ones. It’s kinda wild, when you think about it.

In fact, research done on The Sims 2 (shout-out to Thaddeus Griebel from Dominican University) found that players’ personalities and values often show up in how they play. The game becomes a stage for self-projection: we try on future selves, rehearse relationships, even test fears in a safe, low-stakes environment. I can attest to this directly – I have awful emetophobia (fear of people - or me - barfing up a storm), and sometimes I’d intentionally give my Sims food poisoning just to watch what happened from a distance, frowning and feeling uneasy.

It’s been years since I’ve played like the vengeful chaos god of my childhood. These days, I go long stretches without even thinking about the game, but then every couple of years I’ll pick it up again to see what’s new.

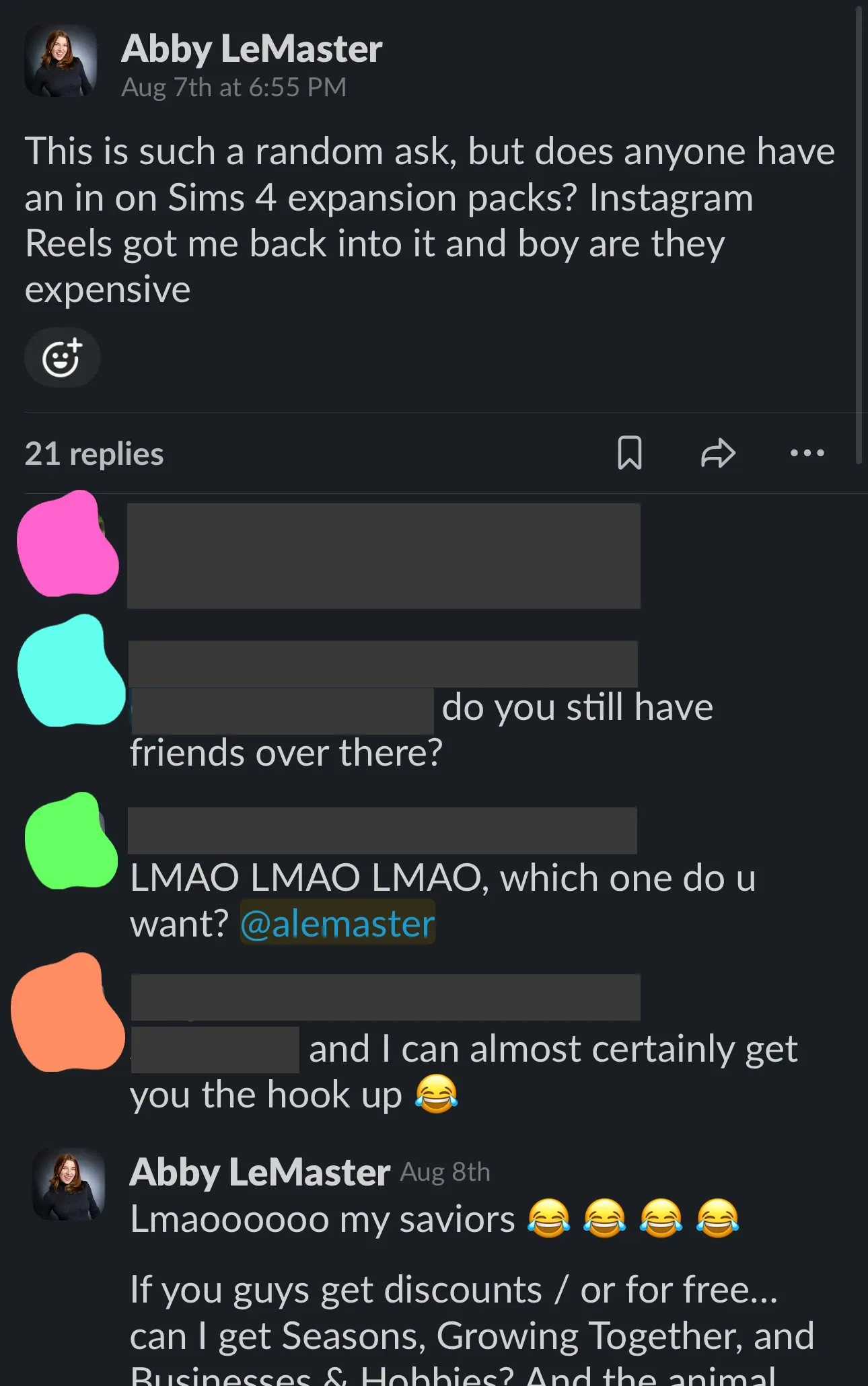

As of now – August 2025 – I’m back into it again. And boy, am I fucked. Like a Ninja Turtle with a crack addiction, I even asked my entire 100+ person team if someone, anyone, had the ol’ EA hookup for a girl who wants to live her virtual dollhouse life (our production director told me I ‘definitely have a special kind of comms brand’ and I’m still trying to figure out if that’s a positive take or not).

Mirror, Mirror

I’ve accomplished a lot since booting up the first game all those years ago. I’ve grown up, for one, entering adulthood with the excitement of someone who truly believed they would unlock the secrets of life at 12:00AM the morning of their 18th birthday. It wasn’t the night-and-day difference I’d envisioned. I still had to wake up early, go to school, and do my chores – only then, I had to go to my job and also pour over stacks of college applications. What did I want to study? What school did I want to go to? Would I like it there, and would they like me? Where would I be placed? Would I qualify for a solo room? What do you mean I need to buy silverware?

Now, at 29, my worries are more existential and involve a bit more nervous finger-twiddling. Am I happy? What kind of legacy do I want to leave behind? Do I even want to stay in the games industry, or are there other facets of life that hold just as much discovery and joy as I’ve found here?

The 11 years between 18 and 29 have seen a few resurgences of my Sims addiction, typically when I start feeling antsy about the direction my life is going. The meta arc of those play sessions is pretty simple – I start out fresh with a household reflective of my own, live through different events, and ultimately quit in horror when someone in the household dies or when I’m faced with a reality I’m not ready to explore.

A year or two into college, I was in a difficult, abusive relationship with a man much older than me (let’s call him “Asshole”). I hadn’t fully admitted to myself how bad it was, but my subconscious was busy doing the work. After reinstalling The Sims during a particularly stressful semester, I created idyllic versions of us.

I remember sitting at my desk in our cramped 525 square foot apartment — half-empty beer bottles scattered on the kitchen counter, the low hum of his video game from the bed — as I pieced together his Sim. My shoulders tensed as I gave him traits that didn’t fit: kind, goofy, a childish streak. It was like putting clothes on a mannequin that I knew didn’t match, but I clicked “accept” anyway. I made him an adult, while I gave myself “young adult.” Even then, the age gap gnawed at me. My stomach tightened, my finger hovered over the mouse, and a little voice in my head whispered: why does this feel wrong?

I played out scenarios I wasn’t brave enough to voice aloud: Should we get married? Have a kid? What would our lives look like if I just went along with the script? On the screen, it all looked neat and tidy, but every time I clicked, the dissonance rang louder. Psychologists talk about “sociodramatic play” as a way kids test boundaries and roles. Turns out, twenty-year-old me was still doing the same thing, just with shinier graphics. Pretend play activates the same empathy circuits in the brain as real life, and mine were firing warning flares.

When Asshole’s Sim inevitably died of old age in my playthrough, I remember the strangest mix of relief and shame flooding my body. Relief, because in that little digital sandbox, the relationship had an end I couldn’t imagine in real life. Shame, because even in fantasy I had dressed him up as something he wasn’t. I knew he wasn’t kind, so why had I made him kind in the game? And in real life, why was I telling other people he was kind, too?

And maybe that’s what made The Sims so unsettling: it was holding up a mirror I didn’t want to look into. It had become a horror game.

So, I stopped playing. It was too real. It would be seven more years before I finally left him, but in that moment, the game let me test-drive what losing control would feel like long before I admitted it out loud. And that’s not just me; culturally, we use games all the time as low-stakes dress rehearsals for the stuff we can’t face head-on. For me, it was an escape hatch. For someone else, it might be Animal Crossing’s debt-free mortgages or Stardew Valley’s safe little farm. Different simulations, same question: what are you not ready to say in real life?

Fleabag: Either everyone feels like this just a little bit and they’re not talking about it, or I am completely fucking alone. Which isn’t fucking funny.

After that relationship ended, I found myself in a much healthier one with someone who was kind, smart, and generous both in and out of the game. My new partner had never played The Sims before, and introducing him to it was a joy. We created our Sims, who eventually had a baby named Kobe (that was the day I learned about “Mamba Mentality”), and even went on virtual vacations. It was lighthearted and fun, a stark contrast to my earlier experiences.

One memory stands out: we hired a babysitter in the game who inevitably neglected our Sim child. In a fit of playful revenge, I showed him how to torture and trap her in a room until she starved. I think I even tried to set her on fire. My partner, a living embodiment of golden retriever energy, watched in horrified fascination. We laughed until our stomachs hurt. And maybe I laughed harder than I should have, because part of me was relieved to feel joy after so long.

But we were only a month or two into our relationship, and it would have been weird to keep playing that household until we knew for sure where we were going to land as a couple. I stopped playing – but not out of frightened dissonance like the last time, but out of tentative hope for what a future could look like. Remember this scene in Avatar? It was basically that.

Katara (me): Well, what if we kissed?

Aang (him): Us, kissing?

Katara (me): See? It was a crazy idea.

Aang (him): Us... kissing.

The COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States soon after, and our late-night games with The Sims turned into longer play sessions of Animal Crossing instead. He grew me a field of flowers, and I made him some sound investments in the game’s Stalk Market. All was well.

When that relationship ended a few years later, I picked up my life and moved to Los Angeles with my cats, Roo and Appa. About a year into living solo in the big city, I picked up the game again. This time, I created a solo household and included the cats so they could join me in-game. My character bought a home in a desert biome, and I spent a lovely, wine-filled evening building a Spanish-style home that felt like a sanctuary. My in-game life mirrored reality – she would go to work, come home, and play with the cats on the couch.

I had a couple of good solo play sessions. My Sim was a writer this time – a career that’s interested me since I was a kid. Maybe that's why I'm writing this. I had a good time.

But when Roo’s Sim inevitably died in-game, it wrecked me. Unlike with humans, the pet death animation was heartbreakingly gentle. She padded across a rainbow bridge, tail high, and greeted death like a new friend. Meanwhile, my Sim was in the shower. She burst out, towel and all, sprinting into the street and screaming at the Grim Reaper. She begged him to bring Roo back. He didn’t, of course. He never does. She collapsed on the ground with wailing sobs. In Roo’s place was a little gray urn on the sidewalk.

I stared at the screen, the hum of my laptop fan the only sound in the apartment, and felt something crack in me. My throat tightened. My palms were actually clammy on the keyboard.

This moment felt darker to me than any of the cruel experiments I’d staged as a kid – darker than drowning Sims in pools or walling them up to starve. Because this time, I hadn’t chosen it. It wasn’t a test of control. It was a test of powerlessness.

Psychologists say pretend play is where kids practice the impossible – the rules of life, death, love, loss. Apparently adults do it too, because there I was, rehearsing grief through a simulation. The Sims was giving me an emotional sandbox to feel the inevitability of loss in a place where nothing “real” was at stake. Except, of course, it felt real.

I tried to keep playing, but it shook me. Eventually I had to stop, unable to face the inevitability of loss. I think I even cried. It was a tough year. Roo, still alive and well, sauntered over to deliver a batch of biscuits and drool.

It’s not just me. Games have become sandboxes for a whole generation to rehearse the things we’re too scared to admit out loud – love, loss, what home means. Some people test it on an island full of talking animals. Some do it in games like Minecraft. I do it in a suburban cul-de-sac with two cats and an infinite money cheat.

Now, years later and on the precipice of 30, I’m playing The Sims again. This time, it’s less about escapism and more about self-discovery. My Sim started out in the game’s equivalent of San Francisco, but very quickly I realized the loft/apartment life was no longer for me. My Sim deserved a goddamn house, but the map didn’t allow for it. Despite all of the cute neighbors and festivals in the area, I realized this version of Abby would need to move far from the concrete jungle in order to find her happiness. Somewhere with grass. Somewhere with trees, and rain.

So, I moved Abby to another map – a place with all of those things. There were less karaoke bars to go to, but hey – she’s pretty good at scrounging for frogs in the woods now. She adopted two cats (I’ve determined never to have mine in the game ever again), who I’ve affectionately named Miro and Jira. I'm a producer, what do you expect? She even met a comedian, and they had a science baby together. I named him after my late brother. In another multiverse, maybe he’s alive and named his daughter after me.

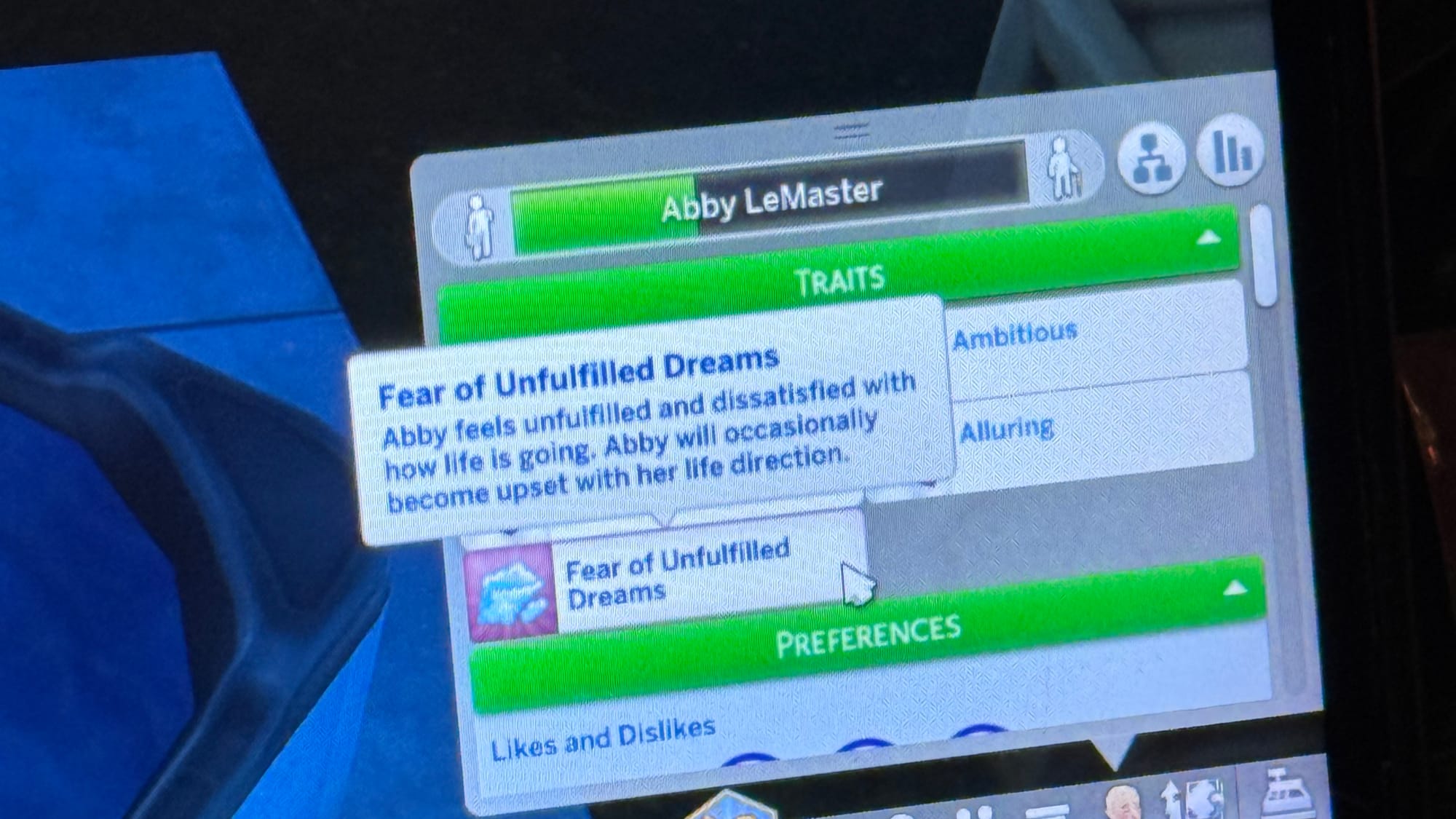

Playing as a happy family has been surprisingly fulfilling. I feel like I’m actually playing forward now instead of recreating the main beats and characters of my life. There are a couple of things happening that are a bit on the nose (“Fear of Unfulfilled Dreams” has popped up in my character's moodlet lately and I’m like, okay, rude), but for the first time I feel like I’m actually playing in a way that feels imaginative and exploratory. I used to force my Sims to work as hard as they could to get to the top of their respective career tracks as fast as possible. Now, they barely work thanks to infinite money cheats. Though this iteration of Abby is on the criminal career path – a jab at the whole Forbes-to-prison pipeline nonsense – she's raking in the big bucks as a minor crime lord. The Boss branch has better work-life balance, so I’m having her pursue that so she can spend all of her time at home building her life with her partner, child, and pets.

The Sims has been with me through the big stuff: chaos, heartbreak, love, loss, and hope. At 8 years old, it was a murder simulator with a laugh track (mine). At twenty, it was a mirror that made me confront what I didn’t want to admit. At nearly thirty, it’s a place where I’m trying to test-drive joy, community, and home (and, okay, maybe a little bit of murder hobo'ing – that part never gets old).

And maybe that’s what this game really is: not just a dollhouse, not just a sandbox, but a mirror. A way to project yourself onto a tiny stage, rearrange the pieces, and see what you learn in the reflection.

For me, that reflection is clearer than ever. I want simplicity. I miss the rain, the trees, and quiet moments of domestic bliss. When I think about the future, I see a cozy house with a front and backyard, overgrown grass, and the sound of rain on the roof. I see myself on a couch with my cats, maybe a dog, and a sense of peace.

I’m tired of high-rise apartment buildings, the sound of highways, and sterile millennial gray walls. I want a space to call my own without compromise. And I want community, safety, and connection. I want these things more than I’ve ever wanted anything else – even my job, as much as I love it, is dwarfed in comparison. When I think about the future, I see love. I see community. I see a life that feels simple and extraordinary at the same time.

In the end, The Sims isn’t just a game to me – it’s become a digital tool for understanding myself and the life I want to build. It’s become a reminder to me that even in a digital world, the things that bring us joy are often the same things we crave in real life.

At eight, I wanted to watch my Sims burn. At thirty, I just want to watch the rain fall outside a window I can call my own. Same sandbox, different self.