This Is What Bad Looks Like

It’s 11:30 PM on a Sunday, and my transformation into Gollum is nearly complete.

I’m crouched by the open refrigerator, half a slice of pizza dangling out of my mouth by my teeth, and I’m trying to wedge a too-big pizza box into a too-small fridge. The box doesn’t fit. I push harder until the door finally clicks shut, then stay there, spine curled like an overcooked shrimp, chewing in silence. It’s greasy, and it gets all over my fingers. The sound of the highway, which remains active even late at night, forms a constant background buzz. My foster dog, an old and crusty terrier mix, snores softly from a hidden spot in the apartment.

Even though I love to cook, I didn’t have the energy to go shopping or meal plan. I’d ordered meal kits earlier in the week – an expensive compromise to make cooking easier – but most of them required an oven. My oven had been broken for three weeks. Getting it fixed should have been simple: log into the maintenance portal, submit a request, and someone would be there within a day. But letting a stranger into my apartment meant exposing the chaos: dirty dishes stacked high, Amazon boxes scattered across the floor, a carpet cleaner full of stagnant water abandoned mid-task. I knew the staff had seen worse, but that didn’t matter. The thought of their polite horror made my chest seize.

So I didn’t file the request. Which meant I couldn’t cook the meals, which meant they spoiled, joining the last batch I hadn’t thrown away. To cook anything else, I’d need clean dishes — but the dishwasher was still full of clean ones I hadn’t put away yet. One blocked task nested inside another, until “make dinner” had become an impossible sequence of prerequisites.

If I really put my mind to it and had the energy, taking on all those tasks at once would take me an hour or two to accomplish. But I don’t, so I don’t. Instead, I skip meals and, by dinnertime, I’ve already lost.

Dinner time comes around. Hungry, tired, and ashamed, I went through the mental calculus again: cook the spoiled food? Wash the dishes? File the maintenance ticket? Every option was too heavy.

The pizza was $30 and just okay – dripping with the kind of grease that tastes good at first but leaves you feeling ill and thirsty later. They only have one size, a large, which doesn’t fit nicely in my refrigerator. But even a gremlin like me knows I need to save it for tomorrow because it will likely be my breakfast and lunch, so I take the box, sit in front of the fridge, and act out the scene above. “Just put it in some Tupperware,” someone might say. “Or even plastic wrap,” another might. But I’ve already sat down, so I’ve already decided I’m shoving it in there whether it makes sense or not.

I finish up. It’s creeping toward midnight when I remember I still need to take my meds — a cocktail of Wellbutrin and Lexapro. I’m supposed to take the former in the morning and the latter at night, but I keep forgetting the morning dose, so I take both in the evenings and hope for the best. Wellbutrin gives me energy, which makes it harder for me to sleep, so I’ve started having a glass or two of wine at night to help me wind down. If I’m out of wine, I’ll take a Xanax. It’s a terrible equation: stimulants in the morning, depressants at night, naps in the middle of the day that throw everything off again. It’s not a sustainable mix – I know that. But burnout doesn’t exactly inspire your best choices. It inspires shortcuts, bandaids, whatever gets you to the next day.

I know that I’m exhausted, but not tired. Sad, but not unhappy. Overwhelmed, irritated, brittle.

Some nights, the noise becomes unbearable. The TV, which I turned on for white noise, suddenly grates. The dog wakes up and paces, his nails click-clicking across the floor before he looks at me with his urgent little expression, which means 'outside, please.' At the same time, my cat, Roo, begins her wailing chorus from the other room – not in pain, just lonely, demanding I fluff her pillow.

And that’s when I break. I sit on the couch, put my head between my knees, cover my ears, and wish for silence. I want everything to go quiet for a little while. I want darkness, stillness, rest — the kind of sleep normal people get without fighting for it.

That night on the kitchen floor wasn’t about pizza. It was about exhaustion so deep that even stowing away leftovers felt impossible. This is what burnout looks like when it leaks into every corner of your life.

When I’m in this state, my brain runs a commentary track: Why can’t you do it? Normal people cook. Normal people clean. Normal people don’t live like this. I spiral into self-loathing. I call myself lazy. I imagine I’m failing at adulthood in ways that are both obvious and shameful.

The Producer Parallel

My therapist diagnosed me with “raging ADHD” a year or two ago, a diagnosis that’s become core to understanding who I am and, more importantly, why I am the way that I am. At the time, it felt like a punchline, but it also explained why I can juggle hundreds of variables at work and then completely collapse at home. It described the gulf between what I know logically (“these tasks aren’t hard”) and what I feel viscerally (“these tasks are impossible”). That distance often feels insurmountable.

The irony is, my actual job is to organize chaos. That’s like, the whole thing.

My career is built on sequencing, prioritizing, and clearing blockers for people and products. I can map out milestones for a hundred developers, anticipate dependencies before they arise, and create frameworks for completing complex projects. I’ve produced feature development, monetization, live ops, restructures, steady-state planning – you name it.

At work, executive functioning is my superpower. At home, it evaporates.

That’s the cruel paradox of burnout. Cooking, dishes, laundry, and unopened mail – the simplest scaffolding of daily life collapses under its own weight.

The Care Task Lens

It helps to name what’s really happening. These aren’t chores in the abstract — they’re care tasks. At their core, they’re just different ways of keeping yourself alive and comfortable.

When I’m burned out, even care tasks collapse under their own weight. Making dinner isn’t just cooking; it’s cleaning old dishes, unloading the dishwasher, scrubbing the counter, and checking if the oven even works. By the time I’ve done the math, it’s easier to order a pizza.

Take mail, for example. To the horror of everyone who knows me, but mostly my old manager (what up, Scott), my “system” is The Bag: a canvas tote where every envelope goes unopened. Bills, junk, insurance forms – all of it swallowed whole until tax season, when I finally dump it on the floor like an archaeologist uncovering a lost civilization.

The shame I attach to that bag is heavier than the paper inside. There’s always a sense of dread – like, what if something important was in here and I missed it? – but mostly it’s just shame. Mail is supposed to be the most straightforward adult task: you open it, you file it, you deal with it.

It’s easy to mistake this for a moral failing. To look at The Bag and think: If I were a responsible person, this wouldn’t exist.

The Shame Loop

When I can’t keep up with the basics, my brain turns cruel. It tells me I’m disgusting, incompetent, and lazy. It whispers that everyone else is managing just fine, and that I am failing in some fundamental way.

I’ve been stuck in this loop for years: perform perfectly → inevitably fall short → collapse → promise to do better → repeat. At work, the cycle drives me to deliver. At home, it just crushes me.

KC Davis captures it perfectly in How to Keep House While Drowning:

“When I viewed getting my life together as a way for trying to atone for the sin of falling apart, I stayed stuck in a shame-fueled cycle of performance, perfectionism, and failure.”

That line hit me like a brick because that’s exactly what I was doing: treating care tasks like penance, as if every dirty dish or unopened letter was a moral failure I had to atone for.

A Survival Framework

Instead of atonement, I began experimenting with survival. When I’m burned out, I come back to this framework:

PRIORITY 1: Body is safe and healthy. Food, water, meds, sleep. That’s the baseline. Sometimes it’s as unglamorous as pizza eaten cold on the kitchen floor – and that counts. Sometimes it’s scheduling a breakfast delivery the night before an early meeting, so I don’t start the day already failing. My body doesn’t care if I use a paper plate or a plastic fork. It just cares that I fed it.

PRIORITY 2: Increase comfort. Comfort makes survival sustainable. Clean sheets after weeks of avoidance. Take out the trash before it becomes a nuisance. Turning off a noise that’s been grating all day. These aren’t chores; they’re acts of mercy toward future me.

PRIORITY 3: Things that make me happy. Burnout flattens joy, so I have to guard the sparks of it. Cuddling my foster dog and lighting a candle and watching something ridiculous on my too-expensive TV (what up, Sam Reich). Happiness isn’t a luxury – it’s a lifeline.

The point isn’t to do everything. It’s to build momentum. Task initiation is often the most challenging part – ADHD, depression, grief, even plain exhaustion can make starting feel impossible. So I look for methods that bypass the barriers instead of trying to bulldoze through them. When shame becomes overwhelming, the only way forward is to lower the bar.

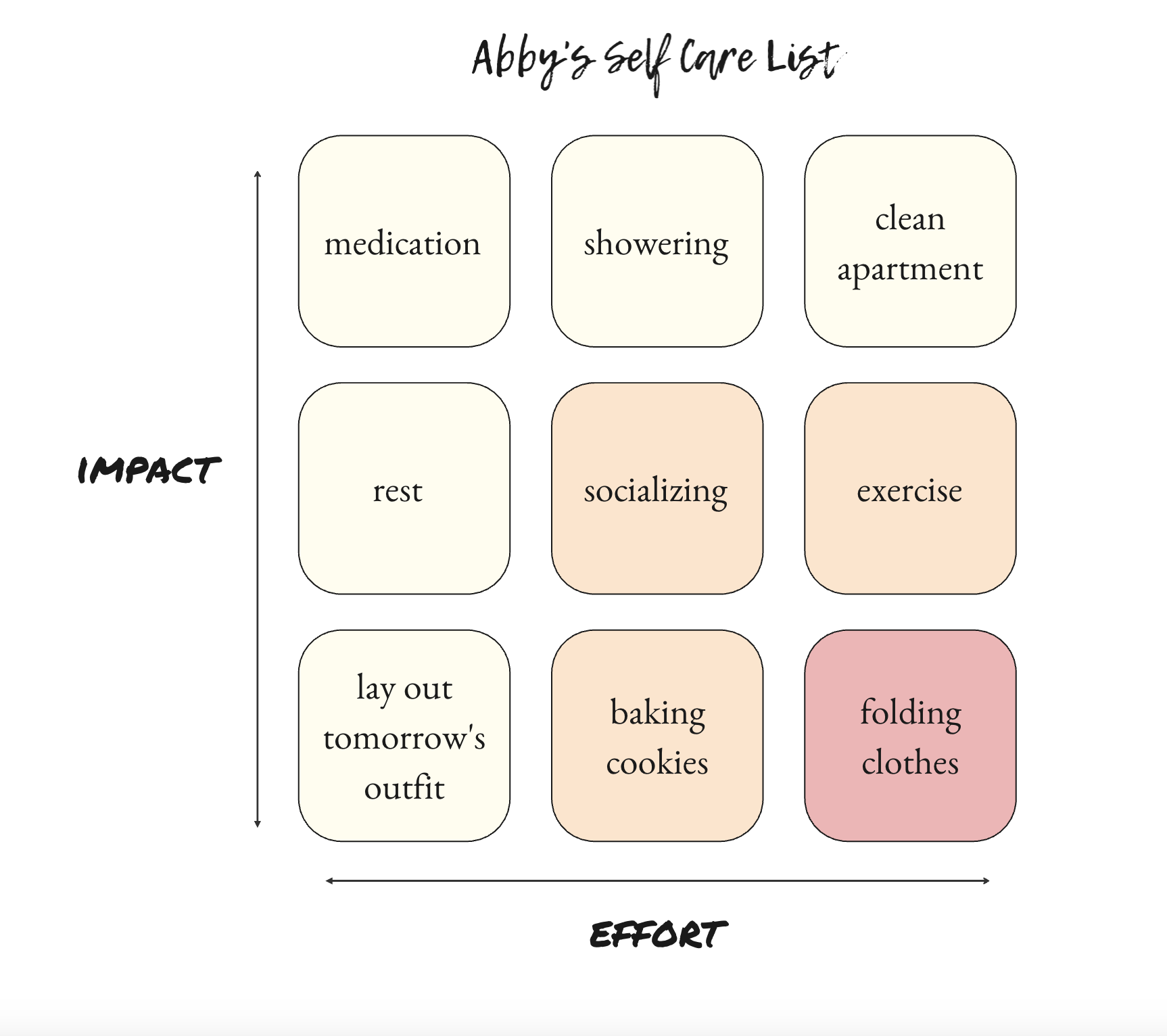

Sometimes that means hacks, like using paper plates for a while to prevent dishes from piling up. A Pomodoro timer to trick my brain into starting. Pre-pasted toothbrushes next to my computer and in my car. A prioritization grid where I can sort tasks by impact and effort, just like I would at work. When I’m burned out, I put the hardest things in a red box and permit myself to ignore them. It’s the only way to keep momentum.

Sometimes it means outsourcing. A cleaner to reset my space when I’m overwhelmed. A laundry service when the pile becomes immovable. Meal kits that may not be cheap but are at least better than eating nothing.

For years, I resisted this because I thought it was shameful to “need help” for things adults are supposed to manage. There were even folks I was close to who bought into this, and I felt like I was spiralling because I didn’t want them to think less of me – or worse, to think I’m spoiled. Now, I try to remind myself: these services exist because someone wants to do this job, and because I’m willing to pay them fairly. It’s not a burden; it’s an opportunity to offer work.

I also recognize that being able to outsource – a meal kit, a laundry service, a cleaner – comes with privilege. Not everyone has the money, time, or safety net to afford such options. For me, getting over the shame of using them was the point — not that they’re accessible to everyone, but that if you do have access, using them isn’t a moral failure. Survival tools vary depending on your specific circumstances. These happen to be mine.

And sometimes it means reframing. The glass vs. plastic ball metaphor is helpful: some things can shatter if dropped, while others will bounce. In a week where I’m juggling too much, I let the plastic balls fall – the unfolded laundry, the unopened mail – and focus on the glass ones: my health, my animals, my meds.

None of these things makes me a better or worse person. They keep me alive. Pizza is morally neutral, damn it. Paper plates are morally neutral. Using what I need to function isn’t wasteful. It’s survival.

But sometimes, burnout doesn’t just leave you with dirty dishes or a bag of mail. Sometimes it carves its message into your body itself.

Burnout Context

During the production of cinematics for The Last of Us Part II, I became so engrossed in my day-to-day tasks that I stopped drinking water. Not consciously – I didn’t want to waste time with bathroom breaks when there was always another file to deliver, another deadline creeping closer. My health was already challenging – and I was a contractor – so I wanted to look like the epitome of productivity. For weeks, I ignored the headaches, the fatigue, and, eventually, the dull ache in my lower back. And then one night, my body broke.

On my 24th birthday, I woke up at 2AM in excruciating pain and pissing blood. I drove myself to a 24-hour urgent care at 3AM in a sketchy part of town, picked up my antibiotics at a pharmacy at 5AM, and then arrived at work at 8AM. I worked eight hours that day instead of twelve, and went home feeling guilty for not working longer.

I didn’t treat it as a warning sign. I treated it as an inconvenience – something to patch quickly so I could get back to being “useful.” I damaged my kidneys badly enough that I still deal with chronic infections to this day.

Looking back, it’s horrifying. At the time, it felt normal. That’s what this industry does: it trains you to override every signal your body sends you. Pain becomes just another blocker to clear. Exhaustion is a scheduling issue, not a symptom.

And the research backs it up. A 2022 study at UC San Diego found that frequent digital interruptions elevate cortisol levels, erode working memory, and keep the body in a semi-permanent state of fight-or-flight. When your nervous system is stuck in survival mode, you can’t rest, can’t focus, and often can’t even recognize how badly you’re hurting until it’s too late.

In games and tech, busyness is currency. You are rewarded for staying late, for grinding, for showing visible productivity at any cost. Rest feels unsafe, even selfish. I’ve seen it at every company I’ve worked for: if you’re not visibly making an impact, you risk being overlooked. I especially remember that feeling back in my contracting days at PlayStation, where job safety meant making yourself irreplaceable at any cost. I sometimes think of it as a kind of “doing addiction”: a day only counts if you can measure it in outputs. Even when you’re sick, even when you’re bleeding, you keep going.

I've decided I don't like that.

Toward a Gentler Framework

When I look back at the moments I’m most ashamed of – and there are plenty – I see a pattern. I’m not failing because I don’t care. I’m failing because I haven’t figured out how to extend the same compassion to myself that I extend to everyone else.

A few years ago, someone I loved fell ill with a stomach bug while I was flying home from Japan. Somewhere over the Pacific, I Instacarted ingredients to my apartment, scheduled to arrive an hour after I landed in LAX. The moment I got home, I made chicken noodle soup from scratch, got in my car, and hand-delivered it to them a few miles away. I’d just gotten off an international flight, was tired out of my mind, and wanted nothing more than to sleep – but it never even occurred to me that I shouldn’t do something to help this person feel better. I will bend myself inside out to care for others. But I would never do that for myself.

Now I’m trying to practice kindness to future me. Not perfection, not a spotless apartment – just small acts of mercy: a glass of water by the bed, a scheduled meal kit, the trash out before it festers. If I can apply my producer strengths inward – grouping tasks into clusters, spotting multiple paths forward, treating problems as solvable puzzles instead of moral failures – I can soften the sharpest edges of burnout.

I know I’m lucky even to have choices about how to take care of myself. But whatever tools you have — whether it’s takeout, a friend who texts you reminders, or just leaving the laundry unfolded — survival still counts.

Some nights, it still looks the same. The fridge is crammed with leftovers in boxes that don’t fit. The sink is stacked with dishes I haven’t washed. The dog snores from the couch while my cat yowls for attention. I sit in the middle of it all, wishing for quiet, wishing for a reset button.

The difference is, I don’t see it as a moral failure anymore. A messy space doesn’t make me a bad person. Forgotten laundry doesn’t erase the ways I care for my team, or the dogs I foster, or the people I mentor. Burnout isn’t laziness; it’s a symptom of being in survival mode for too long.

Learning to give yourself kindness in your personal life should also extend to your work life. I'm notoriously bad at this, but I'm making an effort to improve. For example, I'm writing this on day one of a two-week PTO I scheduled for myself just a little bit ago, a way for me to replenish my energy and think critically about the things I want to do next in a world where the systems that were meant to protect us fail over and over.

I’m still the kind of person who eats cold pizza at midnight on the kitchen floor. I'm also probably going to keep that bag of miscellaneous mail in my closet until the day I die. But I’m also the kind of person who keeps going, who keeps trying, who keeps choosing to care for herself in small and stubborn ways.